Some reviews for This Is Not a Picture Book! have come out. As usual, Publishers Weekly and Kirkus were the first ones, and they both gave my new book (my first with Chronicle) wonderful, starred reviews. More recently, School Library Journal published their own starred review.

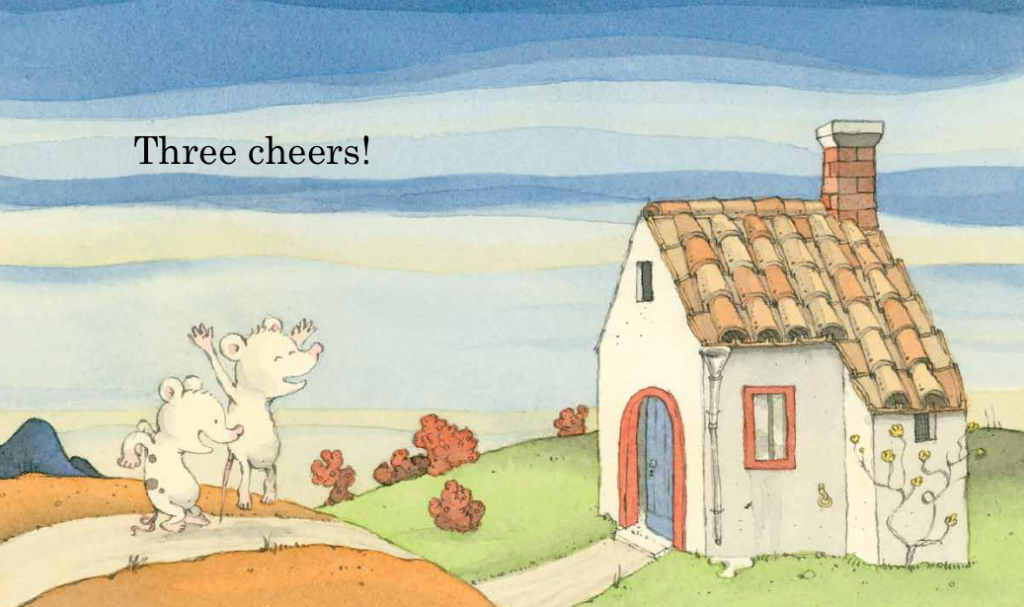

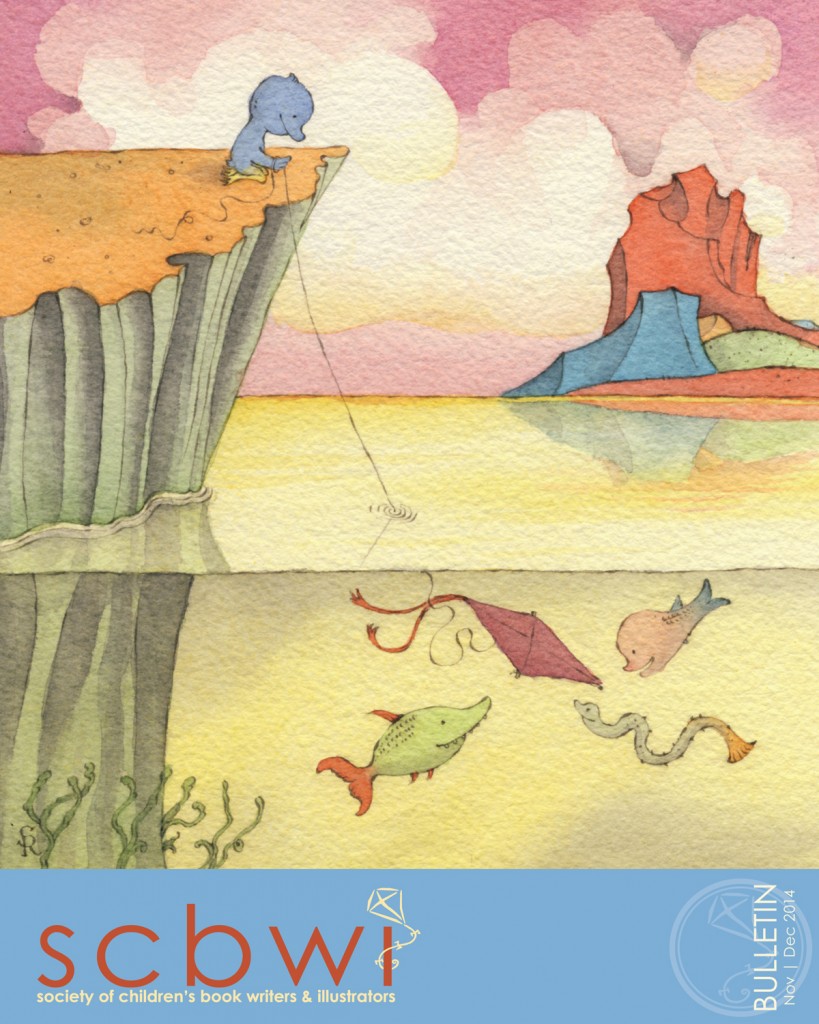

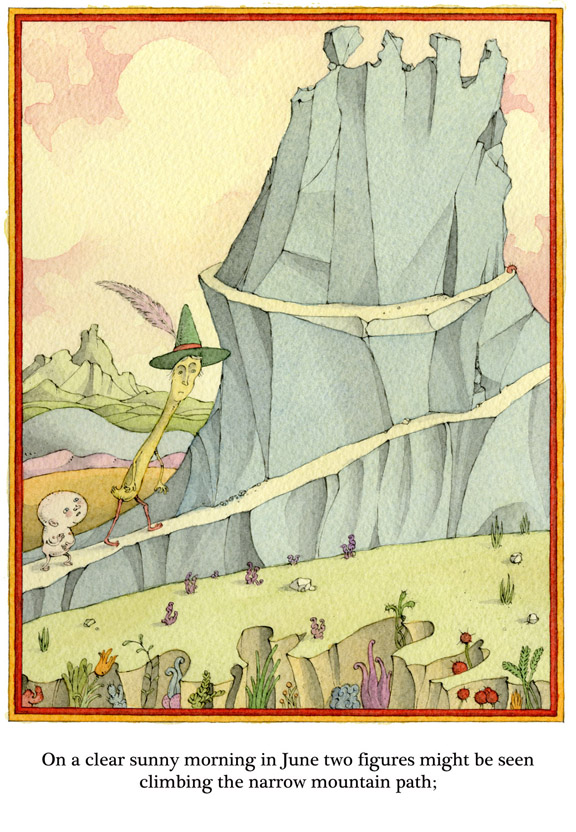

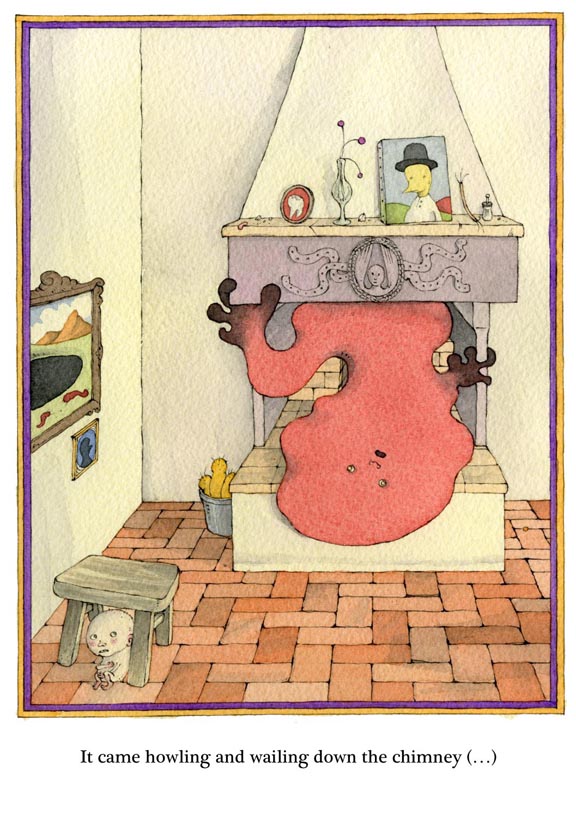

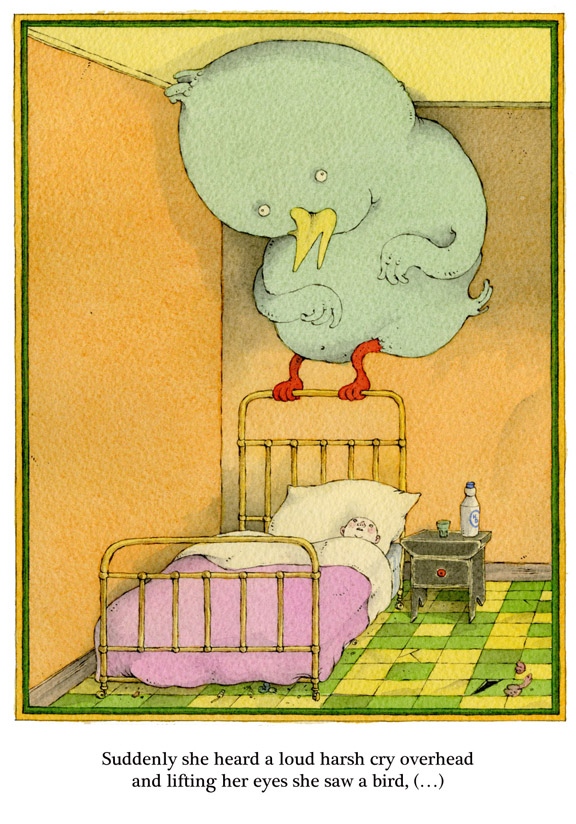

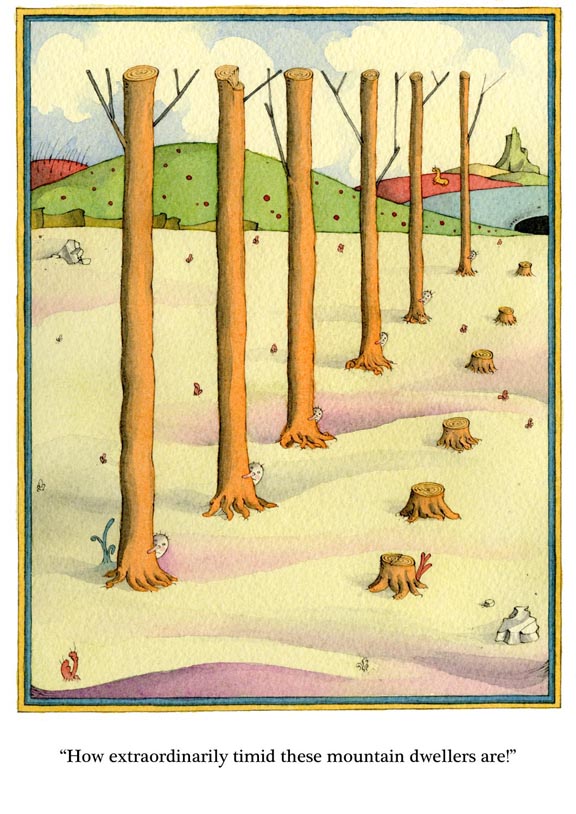

This isn’t a book about books; it’s a book about learning to read. A duckling with a pink beak picks up a fat volume and discovers, in the irritated comment of the title, that it has no pictures. “Can you read it?” asks his sidekick, a bug. “I’m not sure,” says the duckling. “Words are so difficult.” In luminous watercolors, Ruzzier (Two Mice) shows the duckling and bug crossing into a strange, many-colored world, where unfamiliar words are represented as odd machines, blobby shapes, and bizarre creatures. When the duckling stumbles on a word he knows (“bee,” “flower”), its recognizable image pops up among the mysterious ones. Duckling and bug wander through the ever-changing landscape of reading—“There are wild words… and peaceful words”—before landing cozily in bed. Ruzzier’s story offers gentle empathy for kids tackling this intimidating task. Observant readers will note that the endpapers represent learning to read, too; the initial pair retells the story as a beginner might see it, with most of the words scrambled, while the words of the final endpapers read clearly—and no pictures there, either.

And here’s what they think at Kirkus:

A metafictive delight of a picture book.

Alice would be pleased: despite Ruzzier’s title, there are plenty of pictures and ample conversation in this picture book. The titular book within the book, however, is illustration-free. This initially causes distress for the duckling protagonist (who oddly has a bellybutton, but that’s beside the point) who finds the book in the spreads before the title page. When a bug appears and asks, “Can you read it?” the duckling gives it a try. In a brilliant feat of page layout, the recto depicts a green landscape encroaching on the verso, with a log laid across a chasm as a bridge to the white space on which the duckling and bug stand. Their walk across the log is a visual metaphor for the duckling’s successful decoding of the text in its pictureless book. Whole worlds open up to them as the duckling reads aloud. Illustrations depict these worlds evoked by “wild words… / and peaceful words,” and the duckling ultimately declares that “All these words carry you away.” The satisfying conclusion is an affirmation of the transformative power of reading. In one outstanding design touch, the front endpapers tell the not-a-picture-book text in garbled type with transposed letters that one must strain to decode, while the text is clear in its entirety on the back ones.

School Library Journal:

In this winsome examination of the power of words, a little duckling is delighted to find a red book lying on the ground. “Where are the pictures?!” the fuzzy yellow bird exclaims in dismay upon opening it up. The duck flips through the pages, scanning the plethora of print, and begins to recognize some of the words. His interest and enthusiasm flourish as he continues, reading words that are funny and sad, wild and peaceful. His imagination takes off, and along with his tiny cricket friend, the duckling is swept away on a fantastic adventure. He tells the little insect, “All these words carry you away…and then…they bring you home.” The straightforward tale is enhanced by endpapers featuring lines of text, which are jumbled in the front and placed in order to relate the duck’s story in the back. The eclectic pen, ink, and watercolor illustrations add color and energy to the narrative. At first, the pictures are set against a canvas of white space and then slowly expand as the duck begins to envision scenes with each additional word he reads. One of the final spreads portrays the duck and his friend safe at home in his bedroom, which contains a shelf crammed with books.

I can’t wait to know what the others think!