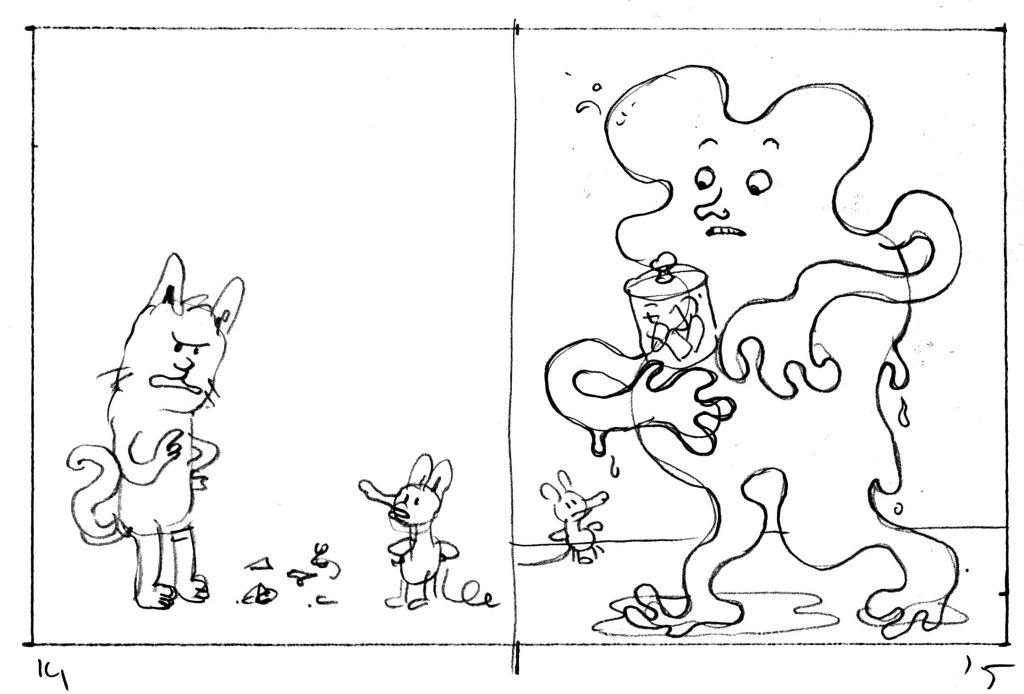

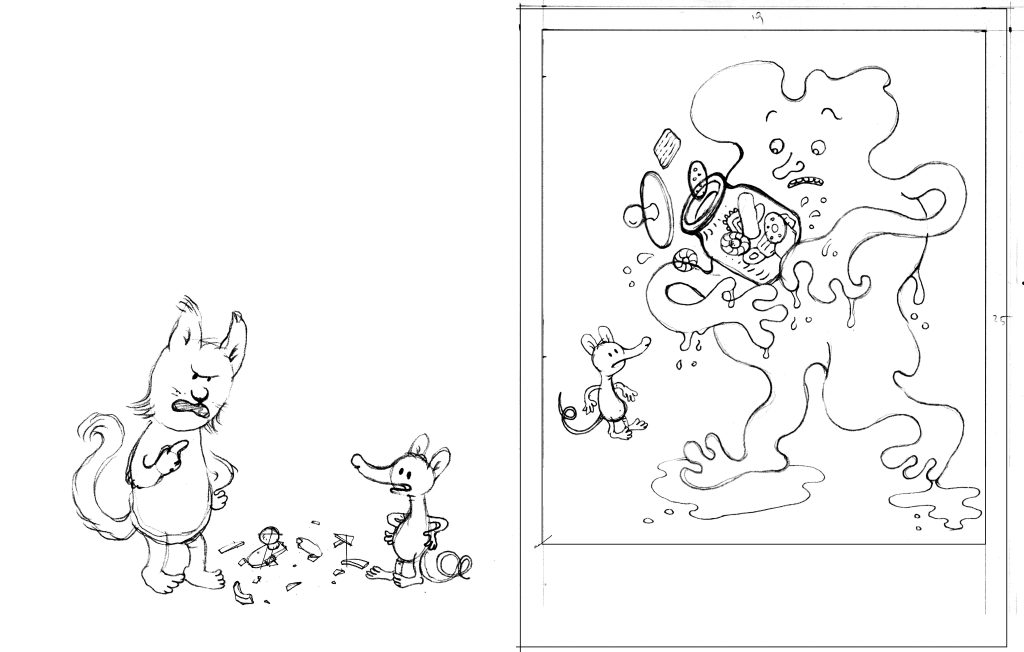

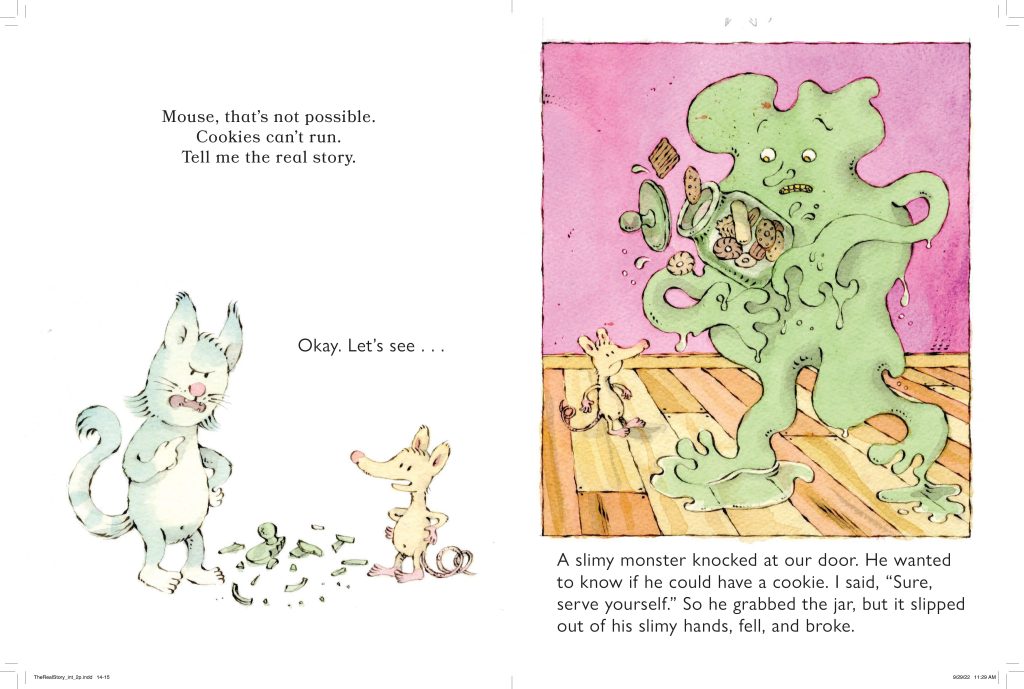

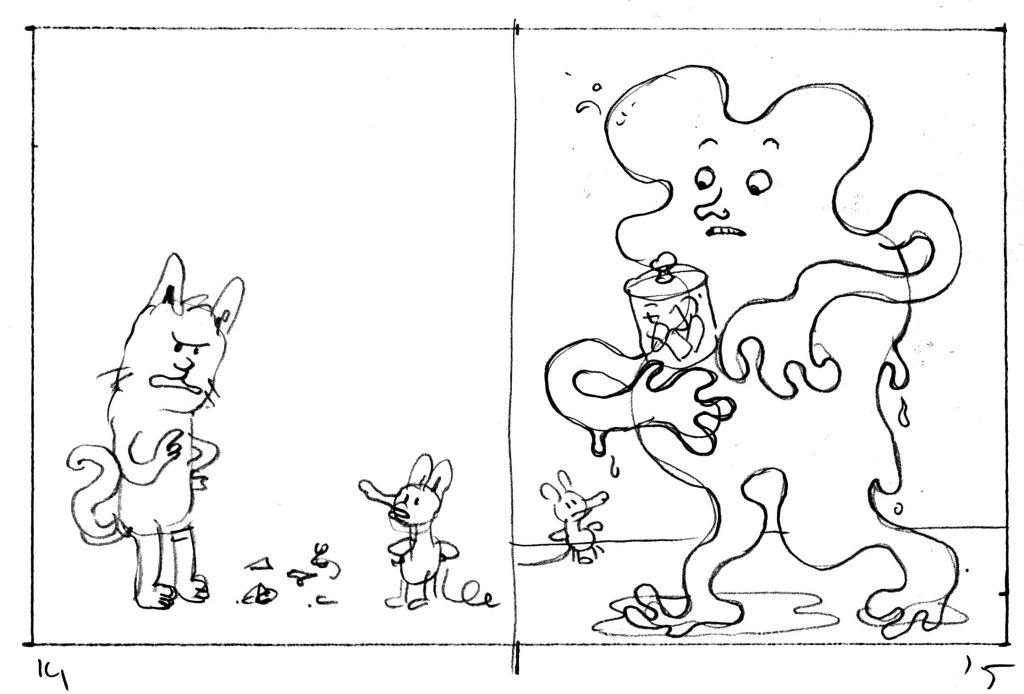

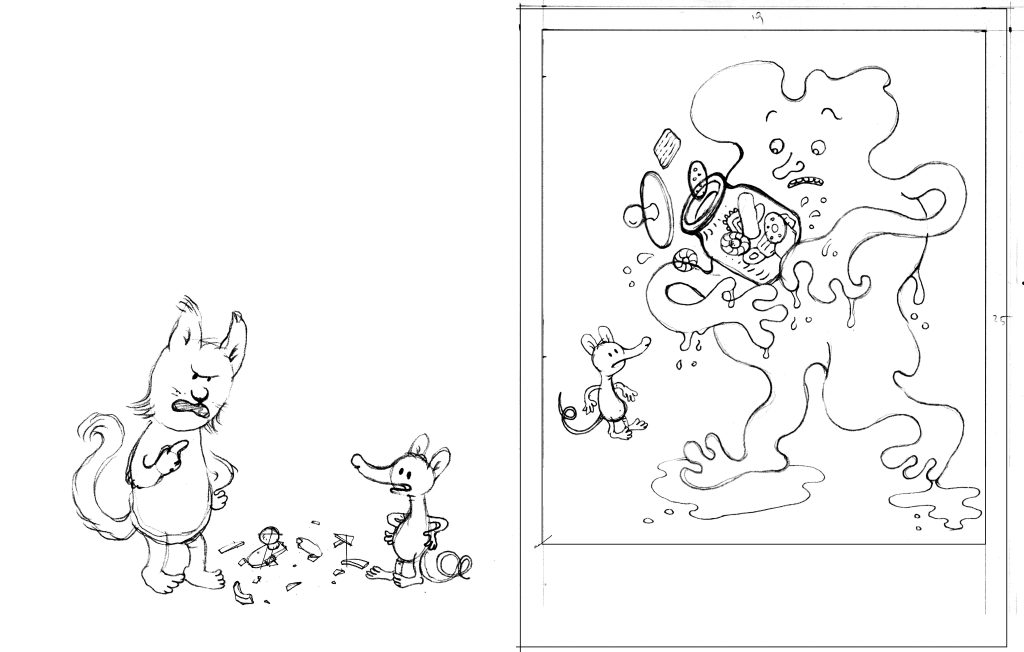

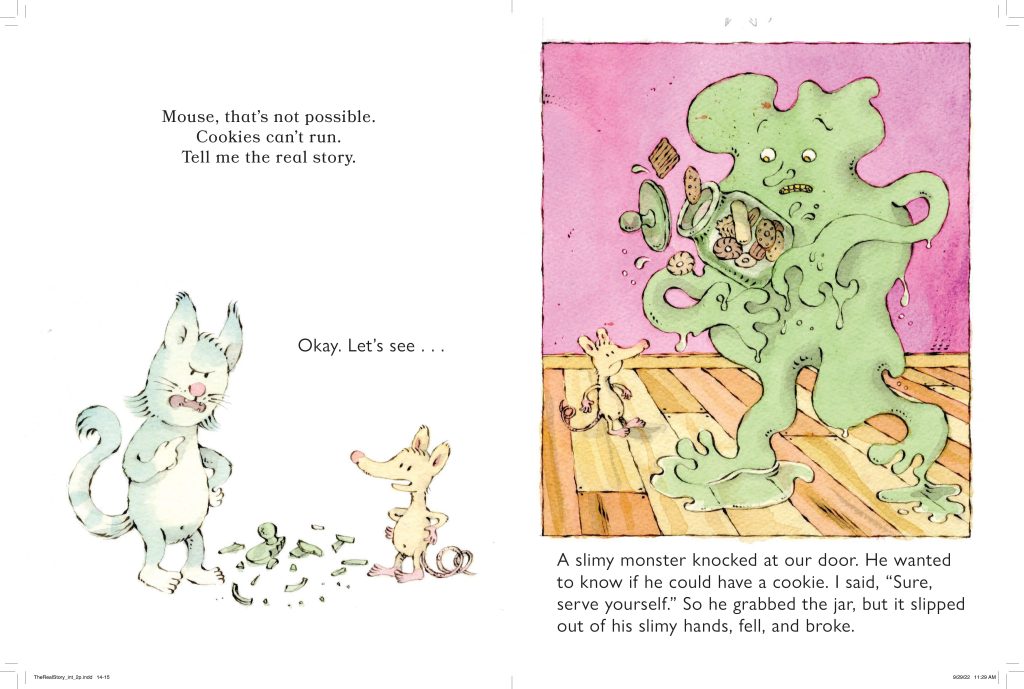

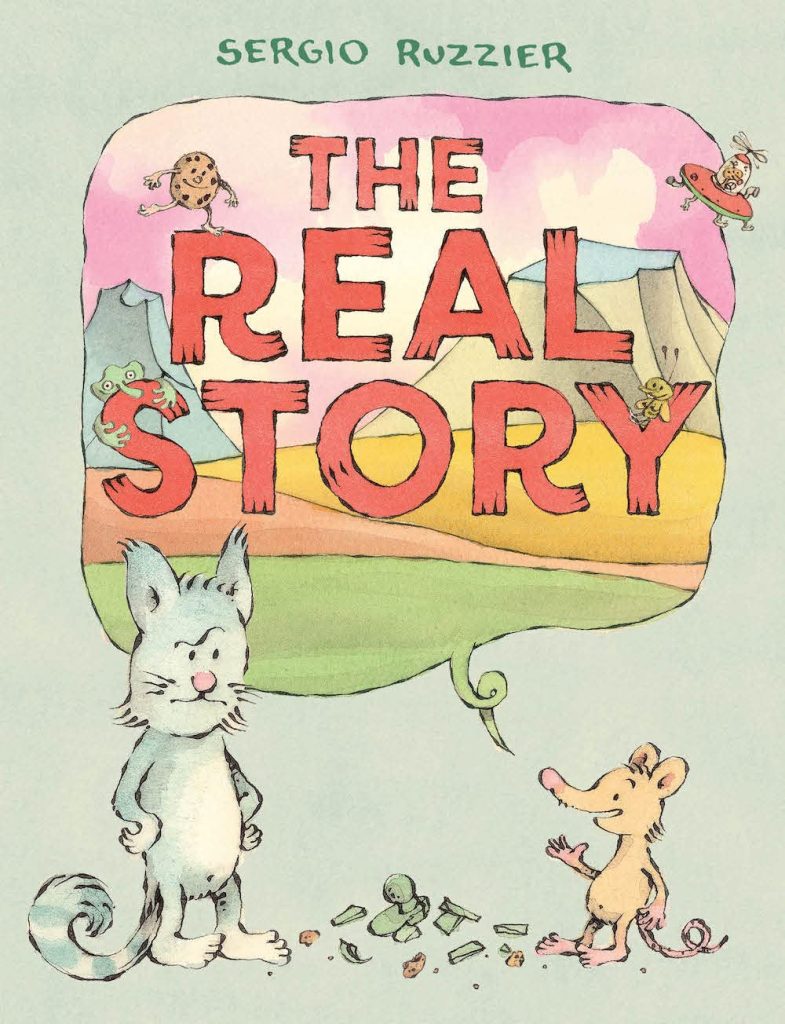

Here are the dummy sketches, the preparatory drawings, and the final pen & ink-and-watercolor illustrations for one spread of The Real Story. Those red splashes on the monster’s head were removed before going to print! Click on image to enlarge.

Here are the dummy sketches, the preparatory drawings, and the final pen & ink-and-watercolor illustrations for one spread of The Real Story. Those red splashes on the monster’s head were removed before going to print! Click on image to enlarge.

“An instant classic!”

“Beloved by generations of readers of all ages!”

“Almost as popular as Bob Shea’s less popular books!”

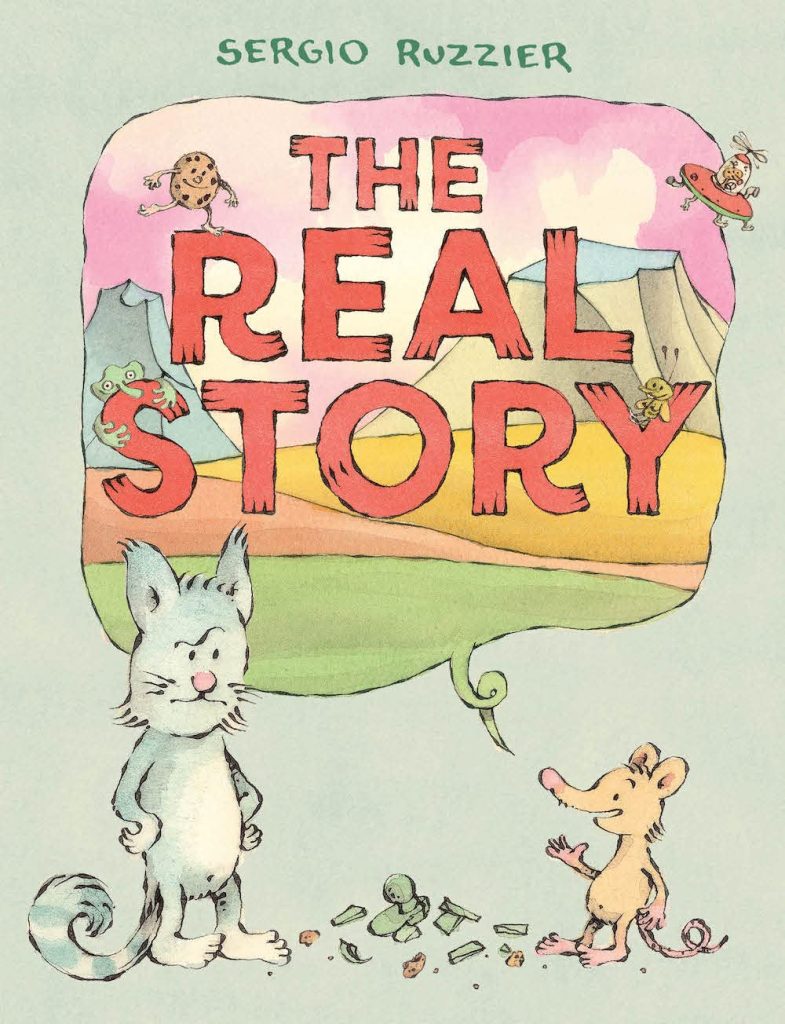

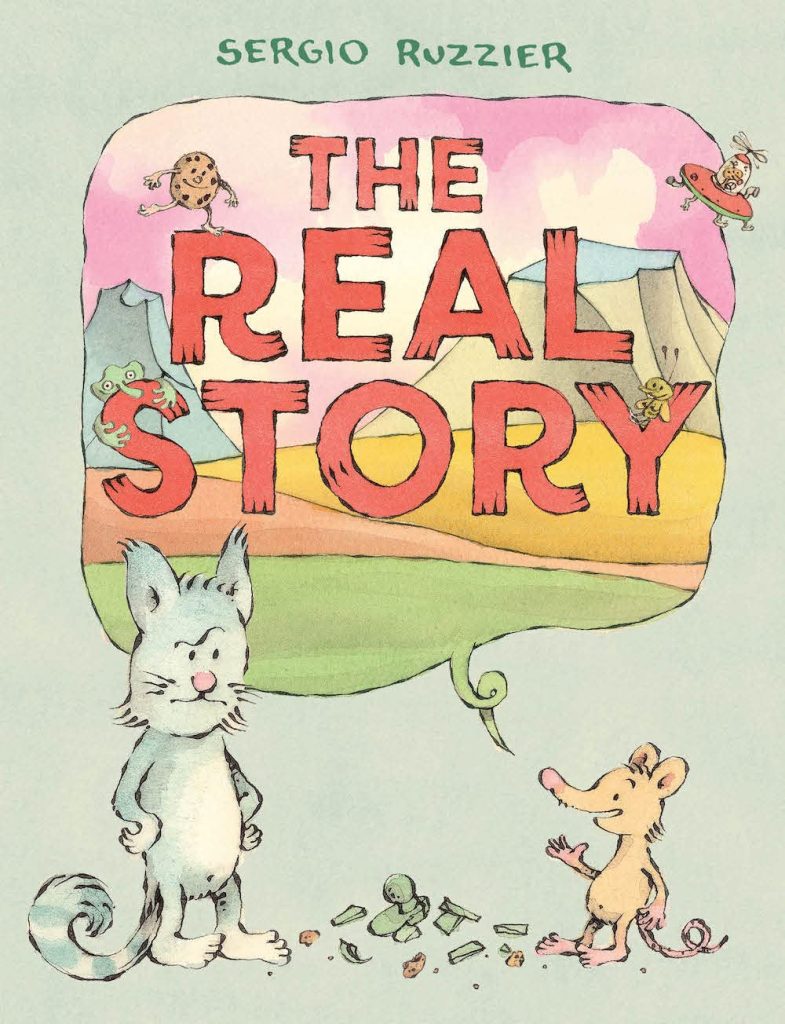

THE REAL STORY

Abrams Appleseed

Available for preorder now, coming out in October.

(Illustration in the first pic generously and unwillingly donated by Thomas Bewick or one of his underpaid assistants.)

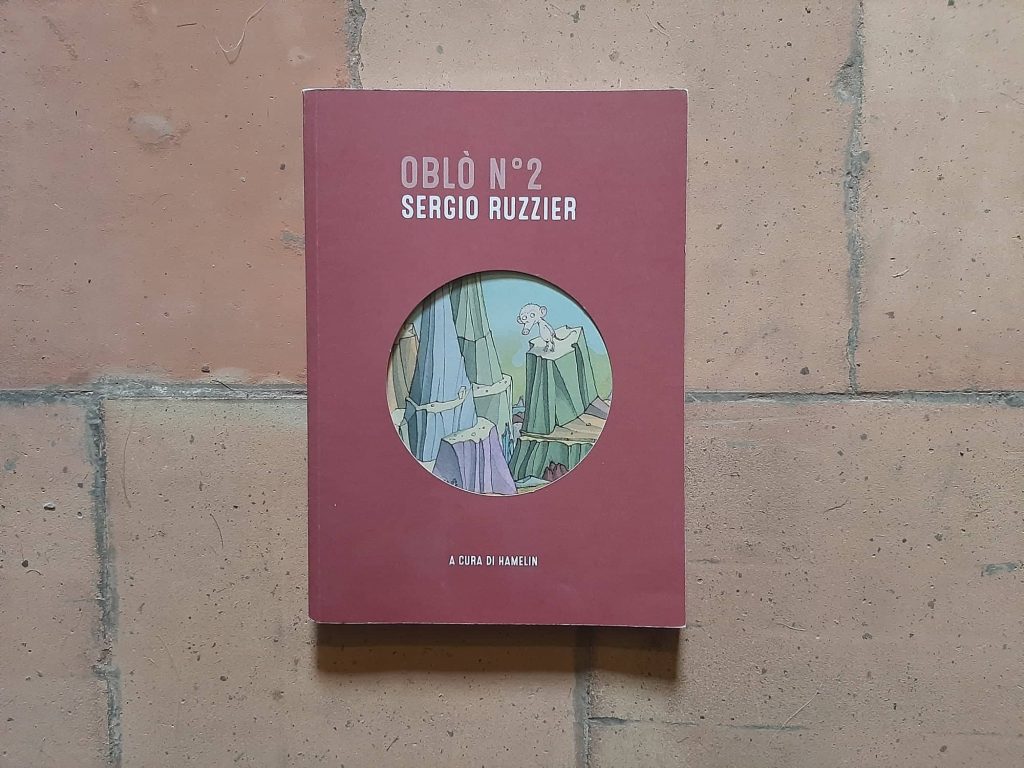

In 2018, the Bologna-based cultural association Hamelin published a monograph on my work, part of their Oblò series. One of the contributors was my friend and colleague Sophie Blackall, who wrote one of the funniest and loveliest things anyone has ever written about me (she has probably regretted it since). The book, of course, is in Italian, including Sophie’s piece. With Sophie’s permission, I’ve decided to share it here in its original English.

In the early days of sharing a studio, Sergio held out his fist. Neither of us is a natural fist bumper, so I was momentarily confused. Instead he dropped a whole walnut into my hand.

Tak! he said.

This is Sergio in a nutshell: surprising, unconventional, funny, endearing, generous and drawn to small, lumpy things.

Our studio is in an old textile factory in an industrial neighborhood of Brooklyn, flanked by a festering canal. There are four of us in the large, sunny room. Sergio’s corner is bright under skylights which sometimes drip when it rains. On those days his corner is shrouded in plastic sheeting, like an old house whose occupants have left for the season.

On sunny days his shelves reveal a collection of treasures given to him by friends, found on the street or bought on eBay. There is a row of unpainted wooden birds in varying sizes. Ducks, chicks, swans, sparrows. There is carved bear whose head opens to reveal an inkwell. Sweet, sad, orphaned stuffed toys huddle together in a corner. On the walls are a collection of vintage postcards of The Mystery Spot, (a gravity defying Californian roadside attraction), a Saul Steinberg print, an Arnold Lobel drawing and a photograph of Sergio, his daughter, Viola and Maurice Sendak.

There are piles of books and piles of papers and piles of drawings, all of which might slide, at any moment, to the floor. (My own space is FAR messier, so I am in no position to judge.) On his desk are medical specimen jars filled with suspicious liquid, actually diluted watercolor paint. There are mugs of pencils and brushes, bottles of india ink and a scattering of discarded nibs. Sergio himself was once described (by an enamored librarian), as dressing like an unmade bed. But the drawings made in this rumpled space are meticulously neat. His pen and ink lines are as fine as any I’ve ever seen. He works on several illustrations simultaneously, balancing them precariously on every available surface, but it has never ended in disaster, (except for that one time with the spilled ink, the only evidence of which is a few tiny black splatters on the far wall…) He paints swiftly, with enviable confidence, seemingly without hesitation and the stack of finished pages towers impressively. The paper, gently buckled from watercolor washes, looks like mediaeval parchment.

Sergio is not plagued with indecision in his work the way the rest of us are, because he is painting a well-defined world. Each book stands on its own, but the characters populate a similar landscape. His illustrations are instantly recognizable for their candy colored mesas and buttes and chalky cliffs. Their pink billowing clouds, stick-like trees and faceted rocks. Their unearthly plants. The perfect geometric tiled floors of their empty rooms.

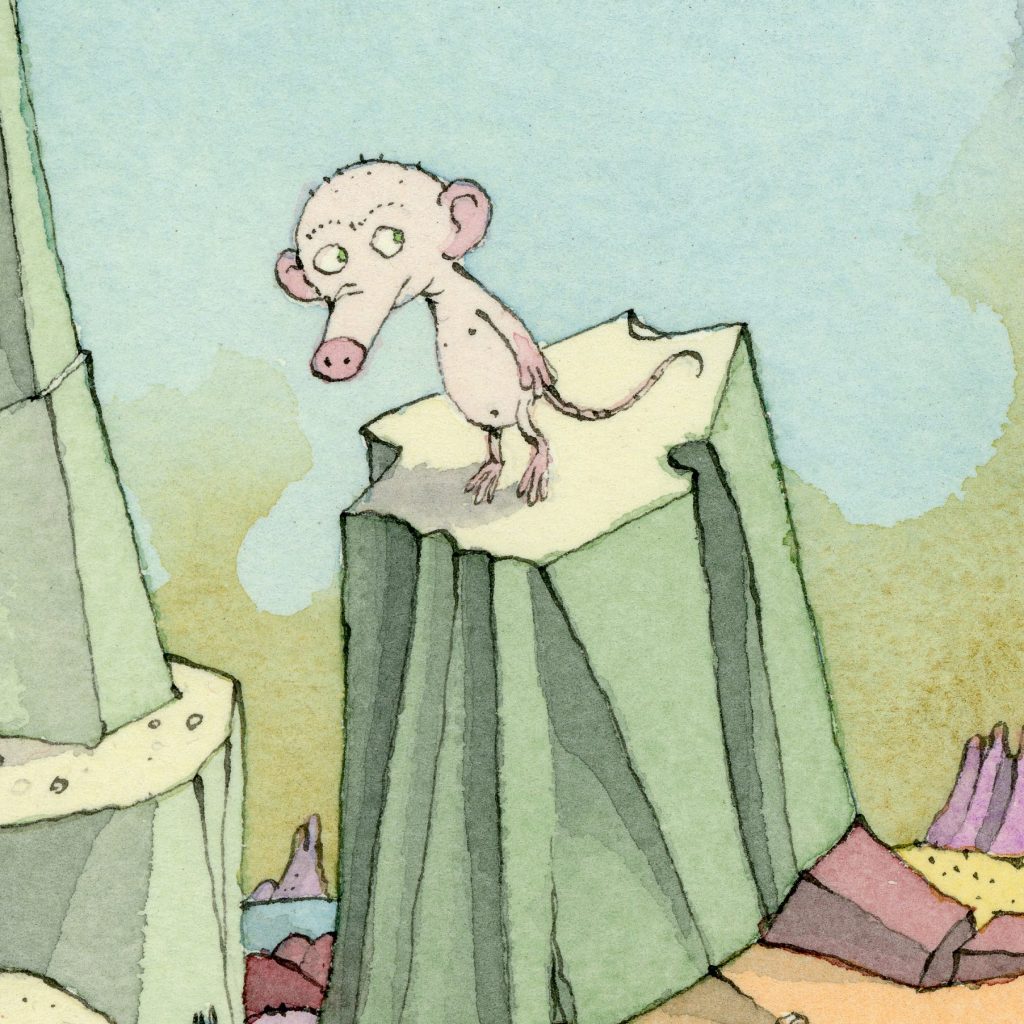

You can imagine the characters from his many books might bump into each other along one of his pebble strewn paths, or find one another peering into a pastel gorge. They might all converge upon a rustic hillside tavern for soup; a party of two mice, a duck, a rabbit, an assortment of melancholy birds, a fox, a weasel, a mole and his grandmother. Not to mention sea monsters, furry snakes, one-eyed fish and the fellow I think is Sergio’s alter-ego, a dear, small pink person, with an elongated piglet’s snout, sticky-out ears, droopy limbs and a rubbery tail.

Speaking of soup, we eat lunch together almost every day in the studio. Recently Sergio carried a large bowl to the table, filled to the brim with soup. It was thick and hearty (literally). He dipped his spoon to retrieve a small round lump.

“You know what this soup is called?” he said, gleefully. “Belly button soup!”

The meat in the soup was sliced chicken hearts. Each slice did indeed resemble a navel, and we, the more squeamish at the table, shuddered. Sergio has an affinity for the grotesque, but somehow he makes it adorable. His books are filled with indescribable lumpy, hairy, fleshy, tumorous, protuberances. They grow from alien plants or roll around under tables. They are unsettling and hilarious and beautiful and repulsive. Sergio never draws human beings, but I think these disembodied lumps are as close as he gets. It is as though he is acknowledging our very worst bits, the most embarrassing parts of our bodies. But he treats them with fondness, putting them on display — albeit lurking in corners, or poking out from under a rug.

Children’s books have become awfully sanitized in recent years. We are afraid of offending parents or librarians, school teachers or book sellers. We are not really worried about children. We know children are unlikely to be offended by the things objected to by the gatekeepers. Sergio’s books are stubbornly and wonderfully unsanitized, and adored by children and the best grownups. He has made his own world and he makes his own rules. Occasionally a concerned publisher might ask him to put a lifejacket on a duck, or clean up some shards of broken glass in case an illustrated chick might cut his illustrated foot, but they usually, wisely concede the point.

Sergio Ruzzier’s stories take place in a dreamy world which is timeless — familiar and comforting but with hints of uncertainty. Beyond that buxom hill might lurk a ravine. His protagonists, in whatever form they take, are small children; like newly hatched birds, they are vulnerable, demanding, contrary, funny, melancholy and incredibly endearing.

But whatever small trials they endure, we know they will come safely home to soup.

With floating belly buttons.

Sophie Blackall

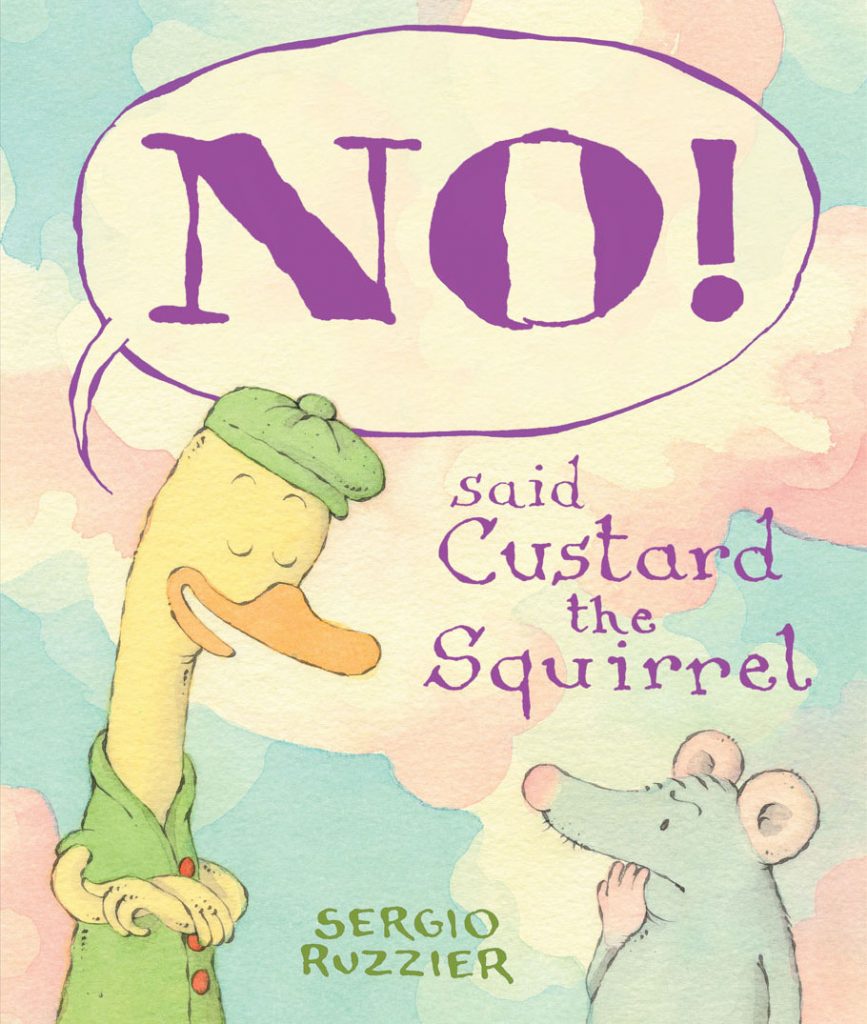

Ruzzier’s trademark artistic style accompanies this tale of defending who you are.

A diapered rodent is remarkably perturbed by Custard the Squirrel. Right off the bat, the rodent asks if Custard is, in fact, a duck. Custard may initially look like a duck to readers, but the refrain—“ ‘No,’ said Custard the Squirrel”—leaves little room for doubt. Still, the rodent just won’t let it go. From numerous angles, the rodent attempts to get Custard to give in and act like a duck. “Won’t you go swim in the lake?” asks the rodent. “Will you please quack?” Custard tirelessly responds in the negative. It is with great grace that Custard remains unflappable in the face of the rodent’s insistence. Finally, by the story’s end, Custard erupts into a chorus of no‘s as joyous as they are adamant. With its steady repetition, this is practically a how-to manual on patiently combating relentless ignorance. Yet it is as much about believing someone when they tell you who they are as it is a guide for dealing with the rodents of the real world. Soft artwork rendered in pen and ink and watercolor deftly highlight the features and body language of both of the main characters. A gently told primer on accepting people for who they are.

It’s rare that I post anything that is not related to books, but after visiting sculptor Filippo Bentivegna’s museum in Sciacca, Sicily, and realizing there is not much online, in English, about him and his work, I decided to publish this short piece and some pictures I took. Like many Italians (including me) did, Bentivegna, born in 1888, emigrated to the United States in 1913, hoping to find a way to make a better living. He lived in New York and settled in Boston. He fell in love with a girl, who apparently had another young man already interested in her. In 1919, during a fight between the two love rivals, Filippo was hit on the head badly enough that the American authorities, considering him unable to work, sent him back to Italy. Back in Sciacca, he went to live in an olive orchard, where he began sculpting heads in stone. He made hundreds of them, creating what he called his kingdom. In town they called him “Filippo the Idiot.” After his death in 1967, his work was left unprotected, and began to be damaged and vandalized. Fortunately, the local authorities finally decided to safeguard such an impressive trove, and the site is now an open-air museum. Here are a few pictures I took during my visit.

I imagine most people interested in children’s books know what happened a few years ago with the legal dispute between the Maurice Sendak estate and the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia. Here is a recap of the whole thing, in case: Libraries, Authors, and Literary Estates: The Complex Case of Rosenbach v. Sendak (2016)

Personally, I think those books that Sendak lovingly collected and was inspired by, should have remained in Ridgefield, CT, in the house where he lived and worked. But a judge decided otherwise and so they ended up at the Rosenbach. At the time of the decision I thought: that’s sad, but at least these books will stay together and will be accessible to anyone who studies or simply loves Sendak and his work. I realize now how naive I was. All those books were just put up for auction by the Rosenbach. I don’t get it. It’s a real shame that such a unique collection will be dismantled, unless someone buys it all and keeps it whole, which is unlikely. It shows closed-mindedness and no respect for Maurice’s life.

I don’t know if this link will still work after the auction is over, but here it is: “Selections from Maurice Sendak’s Personal Collection Sold to Benefit The Rosenbach.”

And here are some of the material, with the descriptions taken from the auction house’s website.

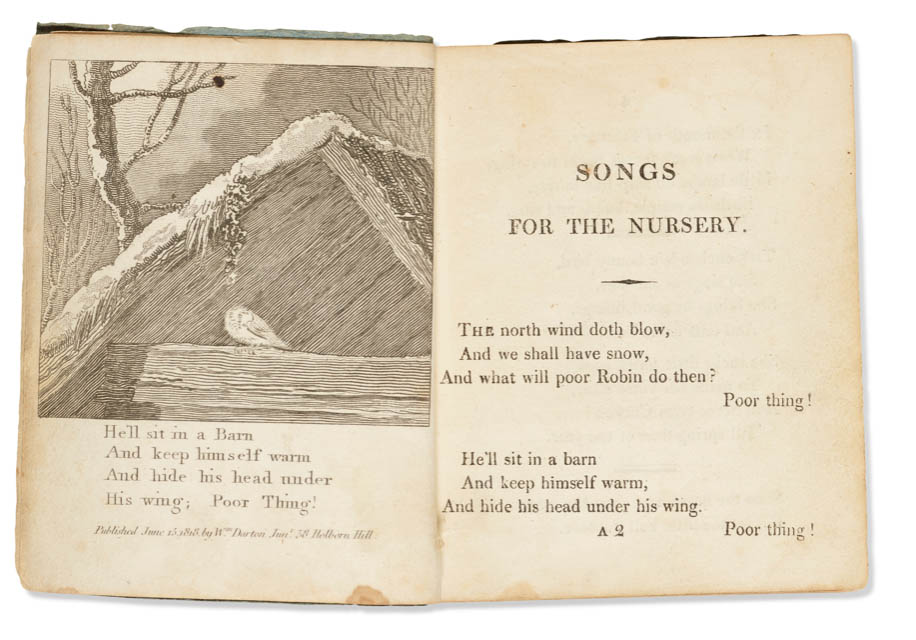

Songs for the Nursery. London: William Darnton, 1822.

The 1822 printing of this rare collection of nursery songs. Includes “Jack and Jill,” Hushabye, Baby,” “Rain, rain go away,” “Pat a Cake,” “Hiccory, Diccory, Dock,” “Little Miss Muffett,” “Old Mother Hubbard,” and many others that have fallen into obscurity. Songs for the Nursery first appeared in 1805 (without illustrations) and printed “Little Miss Muffet” for the first time.

12mo (120 x 95mm). 24 plates dated 15 June 1818, 1 p. ad at rear (one plate with repaired tear through printer’s imprint). (A little minor toning and fingersoiling throughout, ink spot to title page at “S” in “songs”.) Blue paper wrappers (spine toned, a little chipping at ends).

Songs for the Nursery. London: William Darton, 1825.

Rare, with original hand-coloring. Includes many ditties still popular today such as “Jack and Jill,” Hushabye, Baby,” “Rain, rain go away,” “Pat a Cake,” “Hiccory, Diccory, Dock,” “Sing a Song of Sixpence,” and others that have fallen by the cultural wayside.

12mo (132 x 102mm). 24 hand-colored plates dated 15 June 1818. 5 pp. ad at rear. Original muslin, paper printed label (old cloth rebacking, some rubbing, corners bumped).

GRIMM, Wilhelm (1786-1859). Autograph manuscript of a tale, “Liebe Mili” (‘Dear Mili‘), n.p., n.d. [1816].

In German. 134 lines, densely written on 3½ pages, 243 x 206mm, bifolium, a clean copy with a few minor autograph emendations, early annotation at upper margin of p.1 “Wilhelm Grimm 1816” (separating a little along center crease, with two tiny areas of loss measuring no more than 2mm, not affecting any words; a few minor spots of soiling). Custom folder and box. Provenance: reportedly by descent from the recipient; sold at J.A. Stargardt, Marburg, 12 June 1974, lot 638a (DM 12,000) – bought by Bernard H. Breslauer – acquired by the publishers Farrar, Straus & Giroux from Justin Schiller, 1983, and subsequently presented to Maurice Sendak.

A complete tale by Wilhelm Grimm, apparently lost until its rediscovery at auction in 1974. Grimm’s tale begins with a 23-line introductory paragraph in the form of a letter to “Dear Mili,” imagining her throwing a flower into a brook: the flower becomes an analogy of the meeting of minds, and Grimm goes on “Thus does my heart go out to you, and though my eyes have not seen you yet, it loves you and thinks it is sitting beside you. And you say: ‘Tell me a story.’ And it replies: ‘Yes, dear Mili, just listen.'” The tale itself then opens in the traditional style, “Once upon a time there was a widow who lived at the very end of a village…” and relates the story (as summarised by Edwin McDowell, “A Fairy Tale by Grimm Comes to Light,” New York Times, 28 September 1983) of “a mother who sends her daughter into the woods to save her from impending war. The unnamed child … is led by her guardian angel to the hut of an old man who gives her shelter, and whose kindness she repays by serving him faithfully for what she thinks are three days but which are actually thirty years.” She is then returned in safety to her now aged mother, and tale concludes “They sat together the whole evening in great joy, then went to bed serenely and calmly, but the next morning the neighbors found them both dead.”

The manuscript dates from only four years after the first edition of the Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen, and is characteristic of the unsettling tone and apparent moral vacuum of many of the Grimms’s tales. There are no records of an autograph Grimm tale selling at international auction since the present manuscript sold in 1974: according to the catalogue of the Bodmer library, which has an early composite manuscript of 45 tales, “the Brothers Grimm systematically destroyed all the preliminary work for their edition of the fairy tales, probably in order to prevent the comparison between the handwritten versions and later printed edition.” Dear Mili was first published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in 1988, translated by Ralph Manheim, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak.

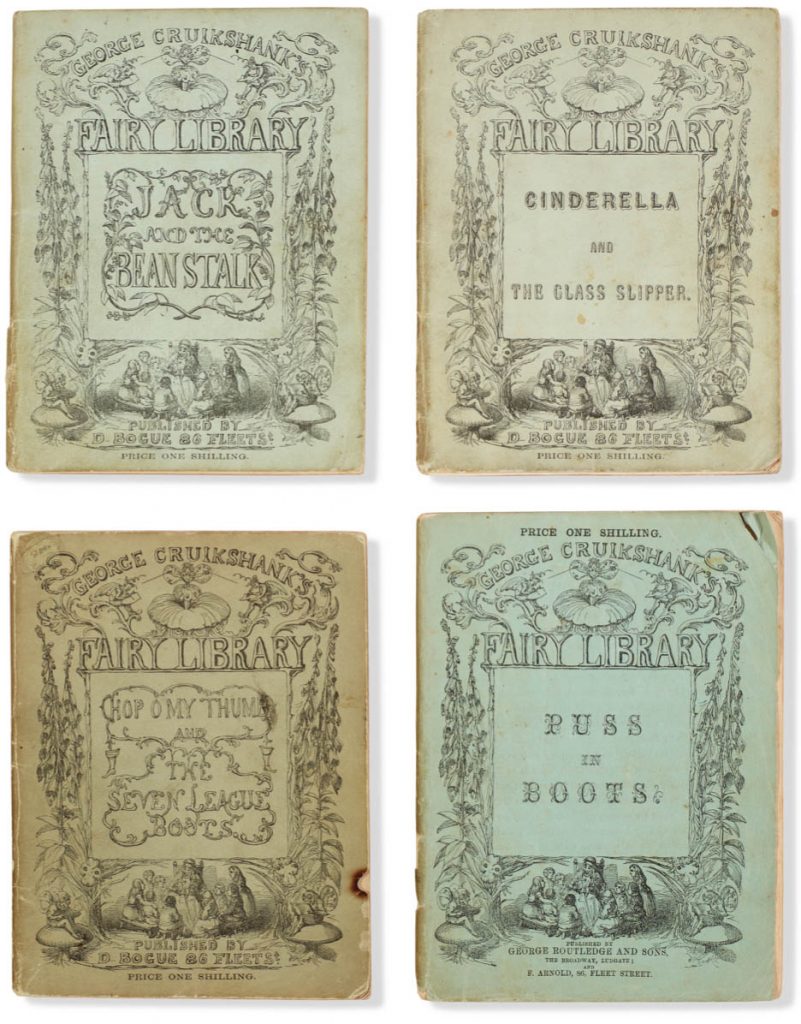

CRUIKSHANK, George (1792-1878). [Fairy Library, comprising:] Hop-O’My-Thumb. London: David Bogue [1853]. [With:] Jack and the Beanstalk. London: David Bogue [1854]. [With:] Cinderella and the Glass Slipper. London: David Bogue [1854]. [With:] Puss in Boots. London: Routledge, Warne and Routledge [1864].

First editions of Cruikshank’s Fairy Library. The first two volumes Hop-O’My-Thumb and Jack and the Beanstalk are first issues, with all of Cohn’s points. Cinderella has two of the three first issue points and Puss has two of the four first issue points. Cohn 196, 197, 198, 199.

Four volumes, octavo (175 x 133mm; Puss: 183 x 135mm). Six plates in each volume as called for, for a total of 24 (a little foxing). Green pictorial wrappers (some soiling, covers starting to detach a little along spines in a couple volumes and small corner of loss to one volume, some general wear). Custom box. Provenance: Henry Bache Smith (bookplate) – Algernon Frederick Hussey (ownership inscription).

GRIMM, Jacob (1785-1863) and GRIMM, Wilhelm (1786-1859). Kinder- und Haus-Märchen. Berlin: G. Reimer, 1819-1822.

Second, expanded edition of Grimm’s fairy tales. The first two volumes include 161 tales plus nine “legends” for a total of 170. The first edition of 1812-1815, by contrast, comprised 156 tales. The contents of the third volume, containing commentary and sources, are new to this edition. It is often lacking from sets both because it was published two years later than the story volumes and because it was of lesser interest to most original owners. This is also the first edition with any illustrations. They are after drawings by the third Grimm brother, Ludwig Emil.

Three volumes, 12mo (128 x 116mm). Illustrated with four copper-engravings, being two additional titles and two frontispieces in the first two volumes, after Ludwig Emil Grimm (a few very minor foxmarks/stains at ends). Contemporary calf (rebacked with old spine laid down, vol. 2 title repaired at inner margin, bound slightly tight). Custom clamshell box.

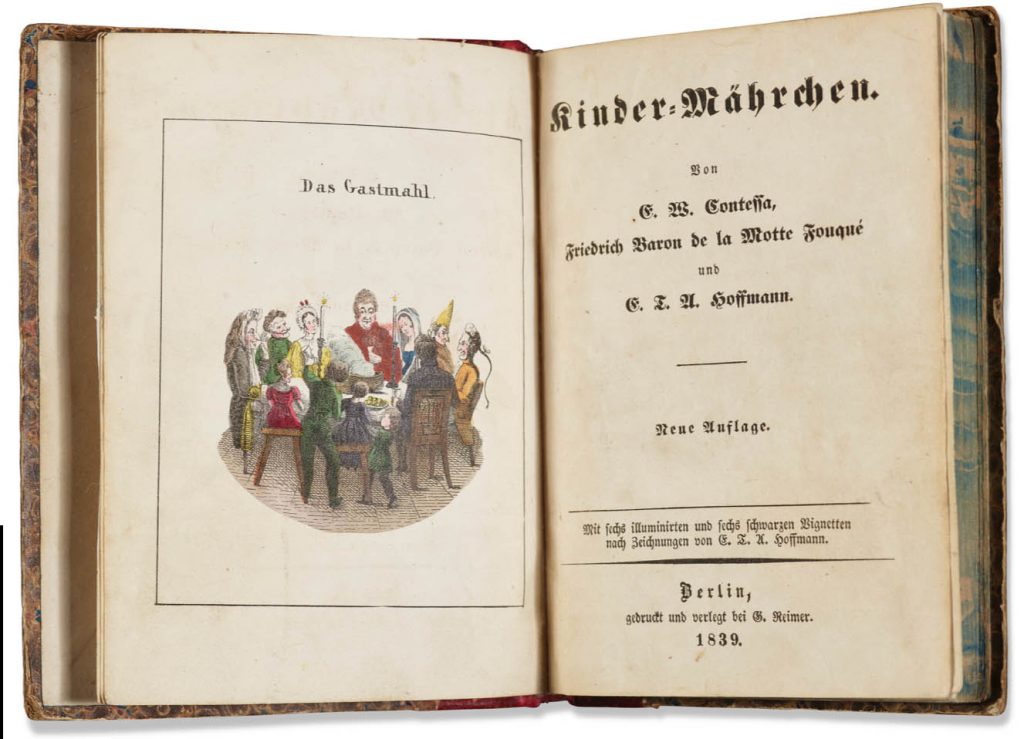

HOFFMANN, E.T.A. (1776-1822), E. W. CONTESSA (1777-1825) and Baron Friedrich DE LA MOTTE FOUQUÉ (1777-1843). Kinder-Mährchen. Berlin: Reimer, 1839.

Second edition, a famous collection of Romantic-era fairy tales, with illustrations by E.T.A. Hoffmann. Hoffmann’s influential unheimlich tales were very important to Sendak. Sendak did the set designs for a 1983 production of the ballet Nutcracker and in 1984 produced a book version of his illustrations of Hoffmann’s story, restoring its darkness and weirdness.

12mo (136 x 103mm). Illustrated with 6 hand-colored plates and 6 woodcut vignettes, after E.T.A. Hoffmann. Contemporary red leather-backed marbled boards (small repairs to spine, some rubbing, hinges showing, repaired chip to f.f.e., two gift inscriptions).

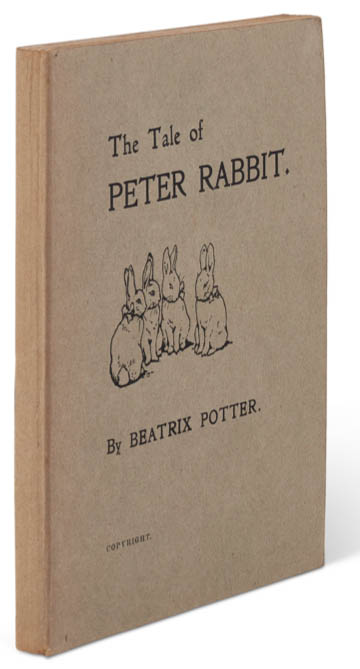

POTTER, Beatrix (1866-1943). The Tale of Peter Rabbit. London: Privately printed, 1901.

Privately printed first edition of Beatrix Potter’s first book, one of only 250 copies of the first issue. “[Potter] sent the manuscript to at least six publishers without success. Finally, in 1901, she decided to have the book privately printed, at her own expense … The books were ready on 16 December and Miss Potter began giving them away to selected friends and relatives and selling them to others at one shilling, two pence each. By this time, however, Beatrix Potter’s career had already been given its first impetus, for the publisher Frederick Warne & Co. had agreed to accept the book for publication in a regular trade edition. But in February 1902, before the trade edition was ready, Miss Potter ordered another 200 copies to be printed of her private edition; this second issue had a rather better binding, with rounded back and darker printed boards” (Gottlieb). The present copy is from the first issue, with a flat spine. Gottlieb/Morgan Library, Early Children’s Books and Their Illustration 220; Grolier Children’s 55; Linder, p. 420; Quinby 1.

12mo. Color frontispiece, monochrome illustrations throughout. Original light grey pictorial boards with a flat spine (some minor foxing to paper edges occasionally visible on pages). Custom chemise and morocco-backed box.

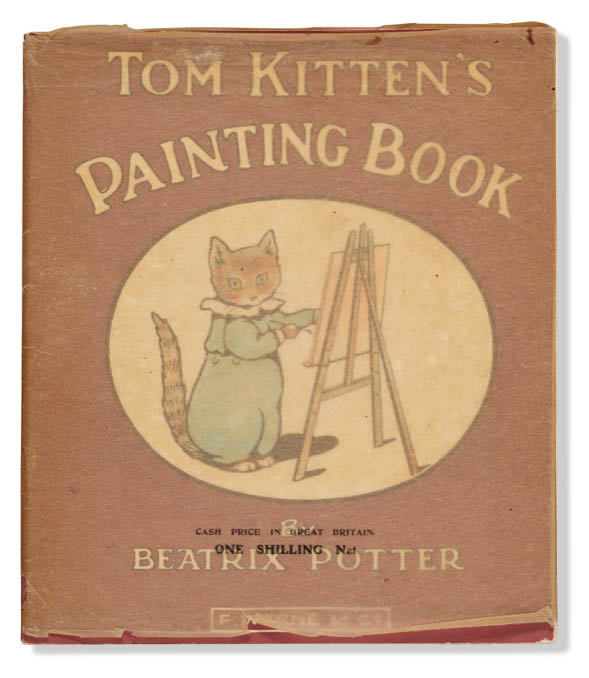

POTTER, Beatrix (1866-1943). Tom Kitten’s Painting Book. London: Frederick Warne [1917].

Very rare and early Beatrix Potter coloring book. The advertisements on the back cover run through The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes (1911); however Quinby gives a date of 1917 because the earliest seen advertisements for this work were on the dust jacket of Appley Dapply. Quinby 24 (not seen, known only from advertisements).

Quarto. Illustrated with eight color plates from eight stories, each with facing “outline” illustration intended for coloring-in. Original color pictorial stiff wrappers (light chipping to spine ends, few marks to lower cover); original printed glassine dust jacket (frayed at edges, lower cover panel with a large chip and some stains).

JOHNSON, Crockett (1906-1975). Harold and the Purple Crayon. New York: Harper & Bros., [1955].

Presentation copy of the first edition, inscribed for Maurice Sendak on the front free endpaper: “To Maury, with fond regards, Crockett Johnson.” The dust jacket shows the price of $1.50 and correct codes, indicating the first edition. Johnson (pen name of David Johnson Leisk) was married to the children’s book author Ruth Krauss. Eight of Krauss’s books were illustrated by Maurice Sendak, beginning with A Hole is to Dig in 1952. This work was published just three years before Harold and the Purple Crayon and is the book which launched Sendak’s career.

12mo (147 x 119mm). Illustrated throughout. Publishers’ cloth-backed pictorial boards, spine lettered in white (light rubbing at edges); pictorial dust jacket (mild wear at extremities). Provenance: Harry Bacon Collamore.